The Battle of Loops: foreach vs. ForEach in C#

Within the realm of C# programming, distinguishing between similar constructs can significantly enhance your coding prowess. This article delves into the comparison of two C# iteration methods: foreach and ForEach. Despite their apparent similarities, they function differently.

The use of ForEach in C# programming has sparked considerable debate. Regardless of whether you embrace its utility or have reservations about it, this article aims to provide valuable insights.

Throughout this article, we will dissect the syntax and performance implications of these methods, equipping you with the knowledge necessary to make well-informed decisions in your C# development journey. We will also explore ways to extend the applicability of ForEach across various collection types and optimize its performance to match that of foreach.

foreach

In C# programming, the foreach statement is a fundamental language feature designed to simplify collection iteration with its straightforward and highly legible syntax:

1

2

3

4

foreach(var value in source)

{

Console.WriteLine(value);

}

ForEach

ForEach is a method offered by the List<T> type in .NET. It requires an action method as a parameter, which in turn takes an argument of type T. When you use ForEach, it invokes the specified action for every item within the source collection.

Here’s an example of how it can be used to write all the items into the console:

1

source.ForEach(static value => Console.WriteLine(value));

Performance Analysis

When it comes to performance considerations, a notable distinction emerges between ‘foreach’ and ForEach.

foreach: This construct can be employed with any enumerable collection. When foreach is used, the C# compiler automatically generates the necessary code to iterate through the source collection. The exact code generated depends on the type of collection being used.

For an in-depth exploration of how

foreachfunctions, please refer to my companion article, titled “Efficient Data Processing: Harnessing C#’s foreach Loop”.

ForEach: ForEach is exclusive to List<T> collections. It is a method provided by List<T>, which grants it direct access to the collection’s internals. ForEach conducts its iteration through the collection by utilizing the indexer on the internal array. This direct access to the internal structure theoretically leads to improved performance. However, this advantage is counterbalanced by the use of a lambda expression to define the logic.

Lambda expressions are delegates, which are reference types. They necessitate allocation on the heap and entail virtual calls. If a lambda requires access to data beyond its scope, it necessitates the use of a “closure”, resulting in the creation of another reference type that must be instantiated on the heap.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of how the use of reference types can impact the performance of collection iteration, I encourage you to explore my other article titled “Performance of Value-Type vs. Reference-Type Enumerators in C#”.

For an evaluation of how these two solutions compare in terms of performance, please refer to the benchmarks provided below.

Extending ForEach to other collection types

The use of ForEach is restricted to List<T> instances because it’s a method specific to this collection type. Despite requests for broader compatibility with other collections, the .NET development team has consistently declined such changes.

However, when dealing with collections other than List<T>, it’s advisable to avoid using the ToList() method as a workaround. This approach involves converting the collection to a list and then using ForEach, but it has significant drawbacks:

1

2

3

source

.ToList()

.ForEach(static value => Console.WriteLine(value));

Using ToList() allocates memory and copies all collection items into a newly created list. This process can be slow and adds pressure to the garbage collector, potentially affecting performance.

If you’d like to understand how

ToList()andToArray()work behind the scenes, please refer to my other article titled “ToList(), or not ToList(), that is the question”.

Instead of depending on ToList(), when you require ForEach functionality with diverse collection types, explore alternative options. You can leverage libraries like MoreLinq, which offer a more comprehensive implementation of ForEach, or craft your own solution.

Let’s construct an extension method for IEnumerable<T> that can be applied to any enumerable implementing it. We’ll name it ForEachEx to prevent naming conflicts:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

static class Extensions

{

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this IEnumerable<T> source, Action<T> action)

{

foreach(var item in source)

action(item);

}

}

You can observe this behavior in action by using SharpLab.

This is an extension method for the interface IEnumerable<T> that, similarly to the List<T> implementation, requires an action method as a parameter, which in turn takes an argument of type T. When you use ForEach, it invokes the specified action for every item within the source collection.

Unfortunately, both this implementation and the MoreLinq version suffer from significant performance drawbacks. They utilize a foreach loop when the source is of type IEnumerable<T>, which represents the worst-case scenario in terms of performance. This approach relies on an IEnumerator<T> enumerator, which happens to be a reference type, further compounding the performance issues.

Refer to my article “Efficient Data Processing: Leveraging C#’s foreach Loop” for an in-depth examination of the inner workings of the

foreachloop and its potential impact on performance.

Arrays and spans

The foreach statement employs the indexer when the source is an array or a span, resulting in improved performance compared to using the enumerator. However, when using the extension method as shown, the compiler loses the ability to optimize this process.

One way to solve this issue is to implement the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

static class Extensions

{

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this IEnumerable<T> source, Action<T> action)

{

if(source.GetType() == typeof(T[]))

{

Unsafe.As<T[]>(source).ForEachEx(action);

}

else

{

foreach(var item in source)

action(item);

}

}

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this T[] source, Action<T> action)

=> source.AsSpan().ForEachEx(action);

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this Span<T> source, Action<T> action)

=> ((ReadOnlySpan<T>)source).ForEachEx(action);

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this ReadOnlySpan<T> source, Action<T> action)

{

foreach(ref readonly var item in source)

action(item);

}

}

You can observe this behavior in action by using SharpLab.

This version includes overloads to handle cases when the source collection is an array or a span. These overloads allow the compiler to call them directly and generate optimized code for foreach loops.

Additionally, an if clause has been added to the enumerable overload to check if the source collection is an array. This enables efficient handling of arrays that have been cast to IEnumerable<T> or any other interface derived from it. Note that this check occurs at runtime and introduces a slight performance penalty.

The type check is executed using GetType() == typeof(...) as recommended in the following comment from the .NET 8 LINQ implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// Use `GetType() == typeof(...)` rather than `is` to avoid cast helpers.

// This is measurably cheaper but does mean we could end up missing some

// rare cases where we could get a span but don't (e.g. a uint[]

// masquerading as an int[]). That's an acceptable tradeoff. The Unsafe

// usage is only after we've validated the exact type; this could be

// changed to a cast in the future if the JIT starts to recognize it.

// We only pay the comparison/branching costs here for super common types

// we expect to be used frequently with LINQ methods.

No checks are made for spans since they cannot implement IEnumerable<T>.

Lists

List<T> already provides its own implementation of ForEach, so adding an extension method seem redundant. However, consider a scenario where a List<T> has been cast to IEnumerable<T> or another interface derived from it. In this case, the first overload of the extension method will be invoked, and it will utilize the reference type enumerator.

To enhance the handling of this situation, we can introduce one more specific case:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

static class Extensions

{

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this IEnumerable<T> source, Action<T> action)

{

if(source.GetType() == typeof(T[]))

{

Unsafe.As<T[]>(source).ForEachEx(action);

}

else if(source.GetType() == typeof(List<T>))

{

Unsafe.As<List<T>>(source).ForEachEx(action);

}

else

{

foreach(var item in source)

action(item);

}

}

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this List<T> source, Action<T> action)

=> CollectionsMarshal.AsSpan(source).ForEachEx(action);

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this T[] source, Action<T> action)

=> source.AsSpan().ForEachEx(action);

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this Span<T> source, Action<T> action)

=> ((ReadOnlySpan<T>)source).ForEachEx(action);

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this ReadOnlySpan<T> source, Action<T> action)

{

foreach(ref readonly var item in source)

action(item);

}

}

You can observe this behavior in action by using SharpLab.

In this updated version, we have the option to call the ForEach method provided by List<T> when working with a casted List<T>. However, instead of calling it, I utilize CollectionsMarshal.AsSpan() to obtain a reference to the list’s internal array as a ReadOnlySpan<T> and call my own extension method.

Unfortunately there’s no generic way to find if a collection can be converted into a span. This way,

List<T>is the only collection to receive this special treatment.

Collections with a value type enumerator

In the .NET framework, all collections are optimized for performance through the use of value-type enumerators. These enumerators are lightweight and efficient, making them ideal for iterating through collections quickly.

The challenge arises when you have a collection, that uses a value-type enumerator, and you want to work with it through a more generic interface, such as IEnumerable<T>. When you cast a collection to such an interface, it’s forced to use a reference-type enumerator instead of the more efficient value-type enumerator. This can result in a performance penalty, particularly in scenarios involving large collections or frequent iterations.

For an in-depth exploration of how the enumerator type can impact collection iteration performance, please refer to my article titled “Performance of Value-Type vs. Reference-Type Enumerators in C#”.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a built-in, generic way in the .NET framework to obtain a value-type enumerator once a collection has been cast to an interface like IEnumerable<T>. This means that developers lose the performance benefits of value-type enumerators when working with collections in a more generic context.

To address this issue, I propose a solution in my article titled “An interface for value-type enumerators, a proposal”. This proposal aims to provide a standardized and efficient way to work with value-type enumerators in a generic manner, improving performance when dealing with collections in various contexts. This potential solution would require its implementation by all collections provided by the framework.

For now, we cannot efficiently handle this case in our custom ForEach implementation.

Value Delegates

Action<T> is a predefined delegate and delegates are references to methods that entail heap allocation and involve virtual calls. This characteristic notably impacts the performance of ForEach in comparison to the more efficient foreach loop. An alternative approach involves utilizing value delegates. While the C# compiler doesn’t automatically generate value delegates, we can manually create them.

Firstly, we need to establish an interface that abstracts the way the action is invoked:

1

2

3

4

public interface IAction<in T>

{

void Invoke(ref readonly T arg);

}

This interface allows us to call a method that takes a single parameter of type T and returns void. It employs ref readonly to ensure the parameter is passed by reference, rather than the default pass by copy method. This enhances efficiency, especially for large value types, with minimal performance overhead in other scenarios. To apply this approach to methods with multiple parameters and/or return values, equivalent interfaces must be created.

In versions prior to C# 12, in had to be used instead of ref readonly. I favor ref readonly because it allows passing ref parameters.

Next, we should refactor the ForEachEx extension methods to accept IAction<T> instead of Action<T>. For instance:

1

2

3

4

5

public static void ForEachEx<T>(this ReadOnlySpan<T> source, IAction<T> action)

{

foreach (ref readonly var item in source)

action.Invoke(in item);

}

However, there is a critical issue with this code. The type of action is cast to IAction<T>, which is a reference type.

Instead, the following modification is required:

1

2

3

4

5

6

public static void ForEachEx<T, TAction>(this ReadOnlySpan<T> source, ref TAction action)

where TAction : struct, IAction<T>

{

foreach (ref readonly var item in source)

action.Invoke(in item);

}

An additional generic parameter, named TAction, is introduced. This parameter specifies the type of the action parameter. Through constraints, we mandate that the generic parameter must be a value type and must implement IAction<T>.

The crucial distinction here is that the compiler now substitutes TAction with the actual type of the provided action. There is no casting involved. The compiler recognizes that the type is a value type with an Invoke() method, allowing for optimization in this scenario.

The action is passed by reference because actions requiring closure must be mutable, and thus, they cannot be passed by copy.

To effectively use value actions, we need to declare the value type that handles the item as needed. For instance, to output items to the console, we can define the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

public readonly struct ConsoleWriteLineValueAction<T> : IAction<T>

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

void IAction<T>.Invoke(ref readonly T item)

=> Console.WriteLine(item);

}

The method Invoke() can be implemented either implicitly or explicitly, as demonstrated. I prefer the explicit implementation because the method is not intended to be called by developers; it should only be accessed by the ForEachEx method.

We can use it as follows:

1

2

var action = new ConsoleWriteLineValueAction<int>();

collection.ForEachEx(ref action);

For a value action that calculates the sum of all items in a collection numerics, we can declare the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

public struct SumValueAction<T> : IAction<T>

where T : struct, IAdditiveIdentity<T, T>, IAdditionOperators<T, T, T>

{

T sum;

public SumValueAction()

{

sum = T.AdditiveIdentity;

}

public readonly T Result

=> sum;

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

void IAction<T>.Invoke(ref readonly T item)

=> sum += item;

}

We can use it as follow:

1

2

3

var action = new SumValueAction<int>();

collection.ForEachEx(ref action);

Console.WriteLine(action.Result);

To achieve this, we need to instantiate a value action, pass it by reference to the ForEachEx method, and then retrieve the result using the action’s Result property. It’s essential to create a fresh instance of the value action for each iteration.

SumValueAction<T>leverages generic math support available in .NET 7, which is further detailed in my other article titled “Generic Math in .NET”. For older versions of .NET, you need to use implementations specific for each numeric type.

Vectorization (SIMD)

Most contemporary CPUs support Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) execution, often referred to as vectorization. Adapting iteration over a ReadOnlySpan<T> can readily harness the vectorization capabilities of a CPU.

For a comprehensive exploration of these features, I invite you to read my other article, “Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) in .NET”.

Vectorization entails performing operations on a vector of data rather than individual data items, necessitating the definition of an action interface that accepts a Vector<T> as a parameter:

1

2

3

4

5

public interface IVectorAction<T> : IAction<T>

where T : struct

{

void Invoke(ref readonly Vector<T> arg);

}

Vectorization aims to maximize the vector’s use, but there may be cases where a remainder of the data must be processed using the standard Invoke() method. This interface must also accommodate scenarios when vectorization is not supported. To address these requirements, the IVectorAction<T> interface derives from IAction<T>, mandating the implementation of both Invoke() methods within the value action.

It’s crucial to emphasize that vectorization is applicable only to value types, so T must be constrained to be a struct.

With this new interface in place, the SumValueAction<T> struct can support vectorization with the following implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

public struct SumValueAction<T> : IVectorAction<T>

where T : struct, IAdditiveIdentity<T, T>, IAdditionOperators<T, T, T>

{

T sum;

Vector<T> sumVector;

public SumValueAction()

{

sum = T.AdditiveIdentity;

sumVector = Vector<T>.Zero;

}

public readonly T Result

=> Vector.Sum(sumVector) + sum;

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

void IAction<T>.Invoke(ref readonly T item)

=> sum += item;

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

void IVectorAction<T>.Invoke(ref readonly Vector<T> vector)

=> sumVector += vector;

}

It’s important to note that this implementation now includes two fields: one for accumulating the sum of individual items and another for the sum of vectorized values. Both fields are initialized to zero in the constructor. The Result property computes the sum of all the items in the vector, plus any items not processed using vectorization. The first Invoke() method remains unchanged, while the second Invoke() method performs addition operations on vectors to accumulate the sum.

The implementation of ForEachEx has been modified to accommodate vectorization support:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

public static void ForEachVectorEx<T, TAction>(this ReadOnlySpan<T> source, ref TAction action)

where T : struct

where TAction : struct, IVectorAction<T>

{

// Check if hardware acceleration is available and supported data

// types for SIMD operations.

if (Vector.IsHardwareAccelerated &&

#if NET7_0_OR_GREATER

Vector<T>.IsSupported &&

#endif

source.Length > Vector<T>.Count)

{

// Cast the source span into vectors of the specified data type.

var vectors = MemoryMarshal.Cast<T, Vector<T>>(source);

// Iterate through the vectors and invoke the action on

// each vector.

foreach (ref readonly var vector in vectors)

action.Invoke(in vector);

// Calculate the remaining elements after processing vectors.

var remaining = source.Length % Vector<T>.Count;

// Reduce the source span to the remaining elements for

// further processing.

source = source[^remaining..];

}

// Iterate through the remaining elements (or all elements

// if not using SIMD operations) and invoke the action on

// each individual element.

foreach (ref readonly var item in source)

{

action.Invoke(in item);

}

}

The use of Vector<T> restricts T to be a struct, which limits this version of ForEach to only work with value types. To maintain compatibility with all types of items, it’s crucial to retain the previous implementation. To prevent naming conflicts, this particular implementation is labeled as ForEachVectorEx. It requires a value action as a parameter, which must implement the IVectorAction<T> interface.

This method will employ SIMD only if the hardware supports it and the number of items is sufficient to fill at least one Vector<T>. First, it casts the span of items into a span of vectors of items, which is an efficient operation that doesn’t involve copying items.

Just like the previous implementation, it calls the action on each iteration but now processes all the vector items simultaneously, using the Invoke() method that accepts a vector as a parameter.

In cases where it’s not possible to use all the items to fill vectors, a few items may be left out. The method calculates the number of remaining items and creates a span containing only these items.

In the end, it iterates through the remaining items (or all items if SIMD operations are not used) and invokes the action on each individual element.

NetFabric.ForEachEx

All the code featured in this article has been thoroughly implemented, tested, and benchmarked to ensure its accuracy and performance. As a result of this extensive work, I’ve decided to release the ForEachEx implementation as a NuGet package, which can be found at the following link: https://www.nuget.org/packages/NetFabric.ForEachEx/

For a more comprehensive exploration of the source code, which includes unit tests and benchmarks, you can visit the repository at: https://github.com/NetFabric/NetFabric.ForEachEx

NetFabric.ForEachEx offers support for both lambda expressions and value actions, providing flexibility to meet various coding requirements. It includes several common value actions, such as writing to the console and summing all the items, and also provides support for vectorization (SIMD) operations.

If you have an interest in optimizing your ForEach operations, consider integrating this package into your project dependencies for seamless and efficient use.

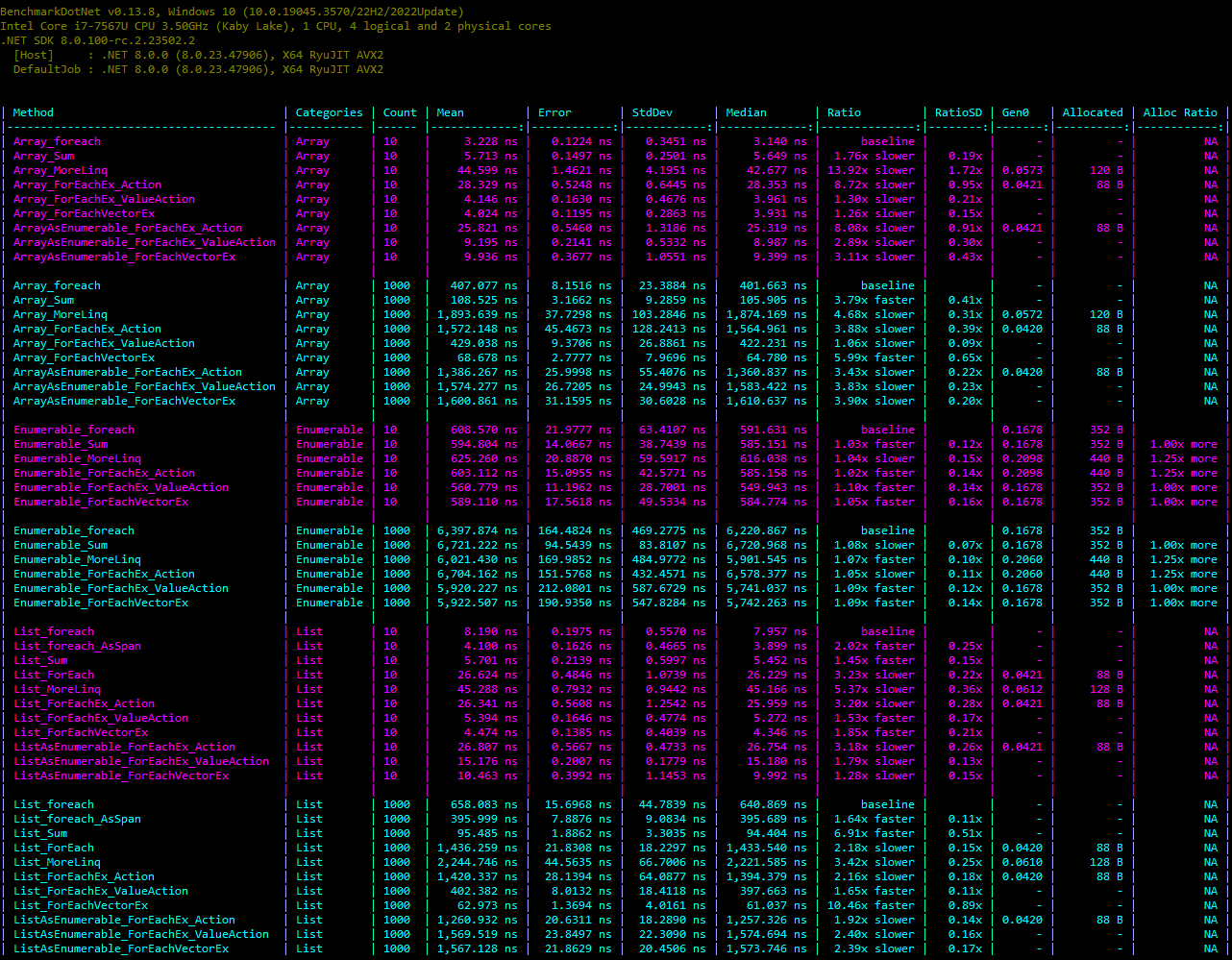

Performance Benchmarks

To evaluate and compare the performance of these various solutions, we will compute the sum of items for multiple collection types, including arrays, enumerables, and lists. We will conduct benchmarks with both small collections consisting of just 10 items and larger collections with 1000 items.

Our baseline measurement employs a traditional foreach loop. The benchmarks also encompass the usage of the ForEach implementation from MoreLinq and the usage of the Sum() method provided by LINQ.

For the ForEachEx implementations, we will benchmark them using both lambda expressions (_ForEachEx_Action) and value actions (_ForEachEx_ValueAction).

You can access the source code for these benchmarks by following this link.

Starting with the List_ForEach benchmark, which assesses the performance of the ForEach method provided by List<T> and compares it to List_foreach, measuring the performance of iterating the same list using a foreach loop, it becomes evident that ForEach is slower. As expected, despite a faster iteration approach, the use of delegates results in reduced performance.

Shifting our focus to the benchmarks for the MoreLinq implementation, which employs an enumerator for iterating the collection, we observe that its performance is similar to other methods when iterating through an enumerable. However, it falls behind other methods when applied to arrays and lists.

Turning our attention to the ForEachEx implementation using lambda expressions (_ForEachEx_Action), we note that it falls behind when compared to using a foreach, owing to the reasons outlined for List_ForEach. Nevertheless, it demonstrates improved performance compared to MoreLinq when applied to arrays or lists.

When examining the ForEachEx implementation utilizing value actions (_ForEachEx_ValueAction), it stands out as faster than other solutions employing lambda expressions. In some instances, it achieves equivalent or even superior performance compared to foreach.

Finally, in the evaluation of the ForEachVectorEx implementation (_ForEachVectorEx), it becomes clear that it outpaces the foreach loop to a significant extent when SIMD hardware is accessible. It even performs better than Sum() provided by LINQ. In .NET 8, both use SIMD for integer items, but the LINQ version handles NaN items and overflows, while the SumValueAction does not address these particular scenarios.

It’s worth noting that the benchmarks indicate that the optimization does not have any effect when arrays or lists are cast to

IEnumerable<T>. I am actively investigating the underlying reasons for this behavior and am currently in the process of developing an updated package to resolve this issue in the near future. Any assistance or insights on this matter would be greatly appreciated.

In terms of heap memory allocations, you see that a lambda expression allocates 88 bytes while a value action does not allocate on the heap. MoreLinq allocates a lambda expression plus an enumerator for all the scenarios used. foreach and ForEachEx only allocate an enumerator when the collection is not an array or a list.

Conclusions

This article seeks to elucidate the disparities between foreach and ForEach. It also delves into an optimized implementation method to mitigate the performance limitations associated with the standard approach.

Even if you have reservations about ForEach, this post endeavors to deepen your understanding of the diverse performance considerations surrounding foreach.

To those who frequently employ ForEach, I hope this article has provided valuable insights into both its limitations and its possibilities.