Behavior Tree Development in C# with IEnumerable and Yield

Coroutines are commonly defined as functions capable of pausing and resuming execution. Managing these requires employing state machines, easily implemented through the use of the yield keyword. However, a challenge arises when composing multiple reusable coroutines, a problem addressed by the concept of behavior trees.

Behavior trees, with practical applications in game development and robotics, offer a modular and reusable approach to specifying agent or robot behavior. Commonly used in these fields, the concept extends to synchronously managing code execution across various computer science domains.

Understanding Behavior Trees

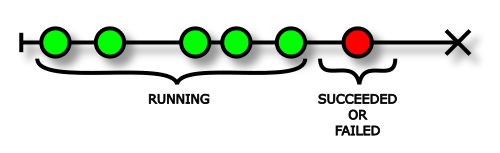

Behavior trees are composed of nodes arranged in a tree structure. Each node acts as a pull stream, initiating processing whenever it’s pulled, representing a behavioral step. During each step, if additional processing is needed, it yields Running. Once no further processing is necessary, it yields either Succeeded if the node completed its task successfully, or Failed if not.

Node Classifications

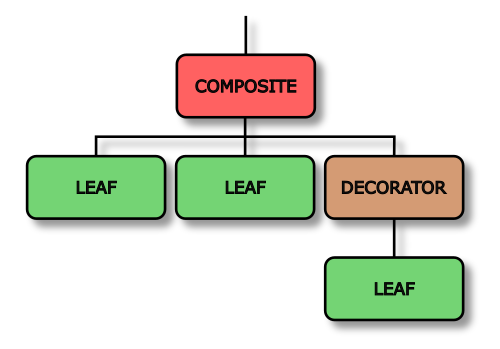

Behavior tree nodes are commonly classified into three main types:

- Composite Nodes: Nodes containing multiple children.

- Decorator Nodes: Nodes with a single child.

- Leaf Nodes: Nodes devoid of children.

Composite and decorator nodes manage the execution flow within their child nodes, controlling how behaviors are executed and enhancing the reusability of behavior tree components. Meanwhile, leaf nodes handle specific operations, including:

- File Operations: Reading from or writing to files on disk.

- Network Communication: Sending or receiving data over a network, such as HTTP requests.

- Database Operations: Interacting with databases, executing queries, or updates.

- User Interface Manipulation: Modifying elements in a GUI, such as updating text or changing colors.

- Logging: Recording events, errors, or other information to a log file or system.

- Hardware Control: Interacting with hardware devices like sensors, actuators, or robotic arms.

- External System Integration: Communicating with external systems, APIs, or services.

- Notification Delivery: Sending notifications, emails, or messages to users or other systems.

- Sensor Data Processing: Analyzing or interpreting data from sensors.

- External Environment Interaction: Triggering events or actions in the physical or virtual environment outside the application.

These examples represent only a subset of potential operations, with specific implementations varying greatly based on the application’s requirements and context within the behavior tree.

Through hierarchical composition in a tree-like structure, complex tasks can be constructed by combining simpler modules. This hierarchical approach offers flexibility and scalability, making it easier to create intricate behaviors and tasks.

Implementing Behavior Trees in C#

There are multiple ways to implement behavior trees in C#. In this section, I’ll describe a minimal approach that takes advantage of the capability of the yield keyword to construct state machines.

Note: For a deeper exploration of the

yieldkeyword’s functionalities, you may refer to my other article titled “Building Custom Iterators with ‘yield’ in C#”.

Node Status Definition

Let’s start by defining a type that encapsulates the three possible statuses of a node:

1

2

3

4

5

6

enum BehaviorStatus

{

Running,

Succeeded,

Failed

};

Node Definitions

In C#, pull streams can be produced using either an enumerable or an enumerator, both conveniently implemented with the yield keyword. The choice between an enumerator and an enumerable depends on the specific requirements of the implementation.

Nodes function as pull streams, represented as an enumerator IEnumerator<BehaviorStatus>. Each behavioral step is initiated by invoking MoveNext() on this enumerator. If MoveNext() returns true, the current behavior status can be accessed via the Current property of the enumerator. However, a return value of false indicates that no further behavior statuses will be provided.

In cases where the behavior node operates until a termination status is reached, using an enumerator is adequate. However, certain scenarios require the repetition of child behavior. Enumerators generated by yield lack an implementation of the Reset() method, leading to a NotSupportedException. On the other hand, invoking GetEnumerator() on an enumerable produced using yield returns a new enumerator instance, initialized to its initial state. This enables the node behavior to be repeated.

Considering these aspects, the behavior tree implementation presented in this article relies on methods returning IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>. This also has the advantage that foreach can be used to both pull the node status and also dispose its enumerator.

Implementing Leaf Nodes

Let’s introduce some basic leaf nodes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> Succeed()

{

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

}

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> Fail()

{

yield return BehaviorStatus.Failed;

}

These nodes straightforwardly yield either Succeeded or Failed status, showcasing the fundamental principles of this approach. Each node is a method returning IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> and employing the yield keyword to produce the status.

Leaf nodes frequently cause side effects. Consider this example, which outputs to the console:

1

2

3

4

5

6

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> WriteLine(string message)

{

Console.WriteLine(message);

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

}

Leaf nodes can also handle more intricate behaviors lasting for multiple behavioral steps. For instance, the following node prints a range of integers to the console, with each line outputted in a behavioral step:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> WriteLineRange(int start, int count)

{

ArgumentOutOfRangeException.ThrowIfNegative(count);

return GetEnumerable(start, count);

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> GetEnumerable(int start, int count)

{

var end = start + count;

for(var value = start; value < end; value++)

{

Console.WriteLine(value);

if(value < end - 1)

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

}

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

}

}

To ensure parameter validation happens during tree definition rather than the initial behavioral step, this method separates the yielding code into an internal method. For more details, refer to my other article explaining this.

The examples provided here use parameter validation methods introduced in .NET 8. For older versions, appropriate equivalent code must be used.

The node validates the parameters and then initiates a for loop, yielding Running with each iteration, pausing until the next behavioral step. Upon reaching the upper limit of value, it yields Succeeded.

These two nodes provide valuable insights into the behavior of a tree. Feel free to experiment with the provided code in SharpLab. Modify the tree definition and observe the resulting output.

Implementing Decorator Nodes

Decorator nodes contain a single child node, passed as a method parameter, and typically modify the behavior of this child node.

Invert

The Invert node reverses the termination status of the child node:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> Invert(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> child)

{

ArgumentNullException.ThrowIfNull(child);

return GetEnumerable(child);

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> GetEnumerable(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> child)

{

foreach(var status in child)

{

switch(status)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Running:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

break;

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Failed;

yield break;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

yield break;

}

}

}

}

This node validates the parameters and then employs a for loop to track the number of repetitions. Within this loop, it iterates over the child’s behavior using a foreach loop to acquire its status. It reacts to each status yielded by the child as follows:

This node uses a foreach loop to iterate over the child’s behavior and acquire its status. It responds to each status yielded by the child as follows:

- If the child yields

Running, this node yields the same, ensuring the child’s behavior continues to be executed. - If the child yields

SucceededorFailed, this node yields the opposite status, effectively reversing the termination status. It usesyield breakin both cases to terminate the behavioral stream.

Repeat

The Repeat node executes the behavior of the child a specified number of times, unless it fails:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> Repeat(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> child, int count)

{

ArgumentNullException.ThrowIfNull(child);

ArgumentOutOfRangeException.ThrowIfNegative(count);

return GetEnumerable(child, count);

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> GetEnumerable(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> child, int count)

{

for(var counter = 0; counter < count; counter++)

{

foreach(var status in child)

{

switch(status)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Running:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

break;

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

goto childSucceeded;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Failed;

yield break;

}

}

childSucceeded:

if(counter < count - 1)

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

}

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

}

}

- If the child yields

Running, this node yields the same, ensuring the child’s behavior continues to be executed and repeated. - If the child yields

Succeeded, this node exits theforeachloop and, if it’s not the last repetition, yieldsRunning, pausing before the next repetition. When another iteration of theforloop occurs, theforeachloop callsGetEnumerator()again, creating a new enumerator instance to repeat the behavior. - If the child yields

Failed, this node yields the same, terminating the behavior with a failure status.

It yields Succeeded when all repetitions have been completed successfuly.

The

gotostatement often sparks debate, but hear me out. Unfortunately, thebreakkeyword can’t be used to break theforeachloop when inside aswitch. To address this, we have a few options: we can unfold theforeachinto awhileloop with a termination flag, expand theswitchinto multipleifstatements, or resort to using agoto. The choice is yours; pick your preferred solution.

RepeatUntilFail

The RepeatUntilFail node continuously repeats the behavior of the child until it fails, resulting in success. This is particularly useful for maintaining this branch of the tree in an infinite loop until a certain condition is met:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> RepeatUntilFail(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> child)

{

ArgumentNullException.ThrowIfNull(child);

return GetEnumerable(child);

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> GetEnumerable(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> child)

{

while(true)

{

foreach(var status in child)

{

switch(status)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Running:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

break;

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

goto childSucceeded;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

yield break;

}

}

childSucceeded:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

}

}

}

This node validates the parameters and then uses an infinite while loop to continually repeat the behavior. Within this loop, it iterates over the child’s behavior using a foreach loop to acquire its status. It responds to each status yielded by the child as follows:

- If the child yields

RunningorSucceeded, this node yieldsRunning, ensuring the child’s behavior continues to be executed and repeated. - If the child yields

Failed, this node yieldsSucceededfollowed byyield break, terminating the repetitions with success.

Implementing Composite Nodes

Composite nodes oversee multiple children, which are passed as a method parameter, and are tasked with managing the execution flow among these child nodes.

Sequence

The Sequence node executes the behavior of its child nodes sequentially until all children succeed or one fails:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> Sequence(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>[] children)

{

ArgumentNullException.ThrowIfNull(children);

return GetEnumerable(children);

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> GetEnumerable(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>[] children)

{

for(var index = 0; index < children.Length; index++)

{

var child = children[index];

foreach(var status in child)

{

switch(status)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Running:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

break;

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

goto childSucceeded;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Failed;

yield break;

}

}

childSucceeded:

if(index < children.Length - 1)

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

}

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

}

}

This node validates the parameters and then uses a for loop to iterate over the children nodes. Within this loop, it uses a foreach loop to step through the behavior of each child and acquire its status. It responds to each status yielded by the child as follows:

- If the child yields

Running, this node yields the same, ensuring the child’s behavior continues to be executed. - If the child yields

Succeeded, this node exits theforeachloop and, if it’s not the last child, yieldsRunning, pausing before moving to the next child. - If the child yields

Failed, this node yields the same followed byyield break, terminating the behavior with failure.

Upon completing all children, it yields Succeeded.

Select

The Select node executes the behavior of its child nodes sequentially until one of the children succeeds. It fails if none of the children succeeds:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> Select(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>[] children)

{

ArgumentNullException.ThrowIfNull(children);

return GetEnumerable(children);

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> GetEnumerable(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>[] children)

{

for(var index = 0; index < children.Length; index++)

{

var child = children[index];

foreach(var status in child)

{

switch(status)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Running:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

break;

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

yield break;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

goto childFailed;

}

}

childFailed:

if(index < children.Length - 1)

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

}

yield return BehaviorStatus.Failed;

}

}

This node is very similar to the Sequence node but with the handling of Succeeded and Failed statuses swapped.

ParallelAny

The ParallelAny node interleaves the execution of the children’s behavior steps, giving the impression of parallel execution. It succeeds or fails when one of the children succeeds or fails, respectively:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> ParallelAny(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>[] children)

{

ArgumentNullException.ThrowIfNull(children);

return GetEnumerable(children);

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> GetEnumerable(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>[] children)

{

var enumerators = new IEnumerator<BehaviorStatus>[children.Length];

for (var index = 0; index < enumerators.Length && index < children.Length; index++)

enumerators[index] = children[index].GetEnumerator();

try

{

while(true)

{

foreach(var enumerator in enumerators)

{

enumerator.MoveNext();

switch(enumerator.Current)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

yield break;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Failed;

yield break;

}

}

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

}

}

finally

{

foreach(var enumerator in enumerators)

enumerator.Dispose();

}

}

}

This node validates the parameters and stores the enumerators of all its children in an array. It then enters an infinite while loop. Within this loop, it iterates through the enumerators array, advancing their respective behaviors by calling MoveNext(). It responds to each status yielded by the child as follows:

- If the child yields

SucceededorFailed, this node yields the same followed byyield break, terminating the behavior with the same outcome as the first child that terminates.

It yields Running only after advancing one step on all of its children. Finally, it disposes of all stored enumerators.

ParallelAll

The ParallelAll node interleaves the execution of the children’s behavior steps, similar to ParallelAny, but it only succeeds after all children have succeeded. It fails if one of the children fails:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

class BehaviorEnumerator

{

public required IEnumerator<BehaviorStatus> Instance { get; init; }

public bool Succeeded { get; set; } = false;

}

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> ParallelAll(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>[] children)

{

ArgumentNullException.ThrowIfNull(children);

return GetEnumerable(children);

static IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> GetEnumerable(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>[] children)

{

var enumerators = new BehaviorEnumerator[children.Length];

for (var index = 0; index < enumerators.Length && index < children.Length; index++)

enumerators[index] = new BehaviorEnumerator { Instance = children[index].GetEnumerator() };

try

{

var succeededCounter = 0;

while(true)

{

foreach(var enumerator in enumerators)

{

if(!enumerator.Succeeded)

{

enumerator.Instance.MoveNext();

switch(enumerator.Instance.Current)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

enumerator.Succeeded = true;

succeededCounter++;

if(succeededCounter == children.Length)

{

yield return BehaviorStatus.Succeeded;

yield break;

}

break;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

yield return BehaviorStatus.Failed;

yield break;

}

}

}

yield return BehaviorStatus.Running;

}

}

finally

{

foreach(var enumerator in enumerators)

enumerator.Instance.Dispose();

}

}

}

Similar to ParallelAny, this node requires storing the enumerators of all its children. In this case, each enumerator also has a flag indicating if the respective node has already succeeded.

The node validates the parameters and stores the enumerators’ information in an array. It then enters an infinite while loop. Within this loop, it iterates through the enumerators array. If the enumerator hasn’t succeeded yet, it steps its respective behavior by calling MoveNext(). It responds to each status yielded by the child as follows:

- If it yields

Succeeded, the flag of this enumerator is updated totrue, and a counter of enumerators that succeeded is incremented. If the counter equals the number of children, meaning all have succeeded, the node yieldsSucceeded. - If it yields

Failed, the node yieldsFailedfollowed byyield break, terminating the behavior with failure.

It only yields Running after advancing one step on all its children. Finally, it disposes of all the stored enumerators.

Defining and Executing a Tree

To define a behavior tree, compose the node methods. Here’s an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

var root = ParallelAll([

Invert(

Repeat(

WriteLineRange(0, 4),

2

)

),

WriteLineRange(10, 10),

]);

The tree employs lazy evaluation, meaning it’s executed only when the root’s status is pulled. For testing purposes, this can be achieved simply using a foreach loop:

1

foreach(var _ in root);

Coroutines and behavior trees are commonly utilized to execute steps at specific moments in the application’s lifecycle, such as before rendering a frame in a game engine. Here’s a possible implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

using(var enumerator = root.GetEnumerator())

{

while(true)

{

// Step through the behavior tree

if(!enumerator.MoveNext())

throw new Exception("Unexpected termination of pull stream");

// Handle termination of the behavior tree

switch(enumerator.Current)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

// Perform actions here

break;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

// Perform actions here

break;

}

// Render frame here

}

}

In Unity, achieving this requires using a coroutine:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

IEnumerator Execute(IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus> root)

{

foreach(var status in root)

{

switch(status)

{

case BehaviorStatus.Running:

yield return null;

break;

case BehaviorStatus.Succeeded:

yield break;

case BehaviorStatus.Failed:

// Perform actions here

break;

}

}

}

Conclusions

The combination of reusable composite and decorator nodes, orchestrating the logic, alongside input and output leaf nodes, facilitates the construction of intricate behaviors with minimal coupling. Employing IEnumerable<T> and the yield keyword in C# proves useful for implementing behavior trees, enabling modular and streamlined traversal of coroutines. This approach enhances decoupling, flexibility, and reusability by allowing the creation of behavior tree nodes that yield sequences of statuses.

By leveraging these capabilities, developers can craft robust behavior trees tailored for diverse applications, thereby improving software efficiency, maintainability, and adaptability. Feel free to experiment with the provided example in SharpLab. Experiment with altering the tree definition and observe the resulting output.