Building Custom Iterators with 'yield' in C#

As detailed in a previous article, an enumerator serves as a representation of a pull stream. To obtain the next item, clients must invoke the MoveNext() method. If it returnstrue, it indicates a successful retrieval, and the value can be accessed through the Current property. The enumerator is typically implemented as a state machine, encompassing information about the current position within the stream and the current value.

On the other hand, an enumerable functions as a factory for enumerators. Each time the GetEnumerator() method is called, it produces a new instance of the enumerator.

These methods can be used explicitly or implicitly, particularly through the use of a foreach loop.

yield return

In C#, the yield return keywords simplifies the implementation of pull streams, allowing it to be used within methods returning one of the enumerable interfaces (IEnumerable, IEnumerable<T>, or IAsyncEnumerable<T>) or one of the enumerator interfaces(IEnumerator, IEnumerator<T>, or IAsyncEnumerator<T>). For instance:

1

2

3

4

5

IEnumerable<int> GetValues()

{

yield return 1;

yield return 2;

}

This method creates a sequence that yields 1, followed by 2, and then concludes. The execution of this method can be understood as follows:

- Start from the beggining of the method.

- Execute until encountering a

yield returnstatement or reaching the end of the method. If ayield returnstatement is encountered, the method yields the provided value; otherwise, stream terminates. - The next time the stream is pulled from, the method resumes execution immediately after the previously executed

yield return. - Go to step 2.

In reality, the method is executed only once, returning an instance of an enumerable where the MoveNext() method and Current property of its enumerator are used to yield the values.

Behind the scenes, the compiler generates the necessary code to implement the required state machine. Utilizing tools like SharpLab, we can see that the method effectively returns an instance of a class like the following (simplified for clarity):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

sealed class GetValues

: IEnumerable<int>

, IEnumerator<int>

{

int state;

int current;

int initialThreadId;

int IEnumerator<int>.Current

=> current;

object IEnumerator.Current

=> current;

public GetValues(int state)

{

this.state = state;

initialThreadId = Environment.CurrentManagedThreadId;

}

void IDisposable.Dispose() {}

bool MoveNext()

{

switch (state)

{

default:

return false;

case 0:

state = -1;

current = 1;

state = 1;

return true;

case 1:

state = -1;

current = 2;

state = 2;

return true;

case 2:

state = -1;

return false;

}

}

bool IEnumerator.MoveNext()

=> MoveNext();

void IEnumerator.Reset()

=> throw new NotSupportedException();

IEnumerator<int> IEnumerable<int>.GetEnumerator()

{

if (state == -2 && initialThreadId == Environment.CurrentManagedThreadId)

{

state = 0;

return this;

}

return new GetValues(0);

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

=> ((IEnumerable<int>)this).GetEnumerator();

}

The crucial aspect to understand is how MoveNext() operates. It performs based on the current value of the state. In cases where the state is 0 or 1, it sets the Current value, transitions to the next state, and returns true. Once state 2 is reached, it transitions to the default state and always returns false, indicating that no more values are available.

The

asyncandawaitkeywords can be explained similarly but return instances ofTask<T>orValueTask<T>instead of enumerables or enumerators.

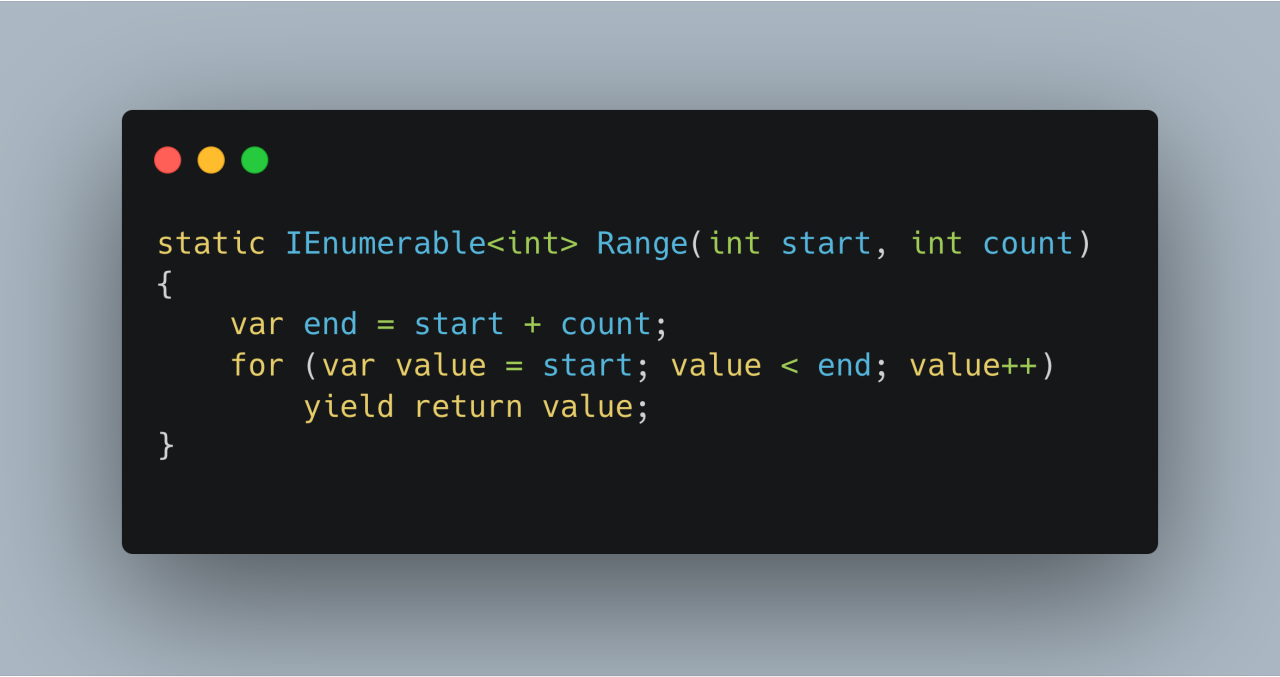

While the presented example is straightforward for better comprehension, real-world state machines can be much more complex. For instance, the Range() method can be implemented to return a sequence of integers:

1

2

3

4

5

6

static IEnumerable<int> Range(int start, int count)

{

var end = start + count;

for (var value = start; value < end; value++)

yield return value;

}

This method repeatedly calls yield return with different values until the end value is reached, terminating the loop and the method. You can experiment with it and see the generated code in SharpLab.

Additionally, asynchronous operations can be integrated with yield. For instance, RangeAsync():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

static async IAsyncEnumerable<int> RangeAsync(int start, int count, int millisecondsDelay)

{

var end = start + count;

for (var value = start; value < end; value++)

{

await Task.Delay(millisecondsDelay).ConfigureAwait(false);

yield return value;

}

}

In this asynchronous scenario, we employ async and await to implement the MoveNextAsync() call without locking, permitting other code segments to execute during the delay. You can experiment with it in SharpLab.

You can also apply yield to process other enumerables, as demonstrated by this implementation of Select():

1

2

3

4

5

static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource, TResult>(IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource, TResult> selector)

{

foreach(var item in source)

yield return selector(item);

}

This method uses a foreach to retrieve the values provided by the source and yields every value transformed by the selector. You can experiment with it in SharpLab. Every pull from this stream, pulls a single value from the source stream.

Also, Where() can be implemented as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

static IEnumerable<T> Where<T>(IEnumerable<T> source, Func<T, bool> predicate)

{

foreach(var item in source)

{

if (predicate(item))

yield return item;

}

}

This method uses a foreach to retrieve the values provided by the source and only yields the values for which the predicate returned true. You can experiment with it in SharpLab. This time, every pull from the this stream, pulls multiple values from the source stream, until one value is returned of there are no more values.

These are basic implementation that help better understand

yield. The implementation of these methods in LINQ are actually more complex because of multiple possible optimizations. Check my other article “LINQ Internals: Speed Optimizations” where I explain the optimizations used.

yield break

In C#, the yield break statement is a valuable tool that allows for the immediate termination of a method’s execution, essentially providing a shortcut that transitions the state machine to its default state. For instance, consider the Empty() method:

1

2

3

4

static IEnumerable<T> Empty<T>()

{

yield break;

}

This method returns an empty stream, and it does so by breaking immediately. As a result, the first call to MoveNext() will return false, indicating that no values are available. You can experiment with it in SharpLab.

Additionally, as an example, here’s an alternative implementation of the Range() method that uses yield break:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

static IEnumerable<int> Range(int start, int count)

{

var value = start;

var end = start + count;

while(true)

{

if (value == end)

yield break;

yield return value;

value++;

}

}

This implementation employs an infinite loop with a yield break statement to terminate it when the specified condition is met. You can experiment with it in SharpLab.

Enumerables vs. enumerators

In C#, a method employing the yield keyword can return either one of the enumerable interfaces (IEnumerable, IEnumerable<T>, or IAsyncEnumerable<T>) or one of the enumerator interfaces (IEnumerator, IEnumerator<T>, or IAsyncEnumerator<T>).

Enumerables act as factories for enumerators, providing a GetEnumerator() or GetAsyncEnumerator() method that produces a new enumerator instance. This design allows enumerables to be iterated multiple times, generating a new enumerator for each iteration. Enumerator implement the actual pull stream behavior.

The foreach loop is applicable only to enumerables, so it is advisable to return an enumerable interface in most cases, ensuring versatility across scenarios. However, when dealing with specific scenarios where a single iteration is guaranteed, returning an enumerator interface is permissible. In such cases, the foreach loop is not applicable, and you must explicitly invoke the enumerator methods and properties.

Here’s an example of when returning IEnumerator:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

var enumerator = GetValues();

try

{

while(enumerator.MoveNext())

{

Console.WriteLine(enumerator.Current);

}

}

finally

{

if (enumerator is IDisposable disposable)

disposable.Dispose();

}

static IEnumerator GetValues()

{

yield return 1;

yield return 2;

}

Just invoke MoveNext() within a while loop and retrieve the value returned by Current. It’s usually advisable to verify if the enumerator is disposable and dispose it after the iteration is complete. The finally block ensures this happens even if the while block throws an exception.

Here’s an example of when returning IEnumerator<T>:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

using(var enumerator = GetValues())

{

while(enumerator.MoveNext())

{

Console.WriteLine(enumerator.Current);

}

}

static IEnumerator<int> GetValues()

{

yield return 1;

yield return 2;

}

IEnumerator<T> inherits from IDisposable, ensuring the enumerator is always disposable. A using block can be used to guarantee the dispose of the enumerator.

Here’s an example of when returning IAsyncEnumerator<T>:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

var enumerator = GetValues();

await using(enumerator.ConfigureAwait(false))

{

while(await enumerator.MoveNextAsync().ConfigureAwait(false))

{

Console.WriteLine(enumerator.Current);

}

}

async IAsyncEnumerator<int> GetValues()

{

yield return 1;

await Task.Delay(1).ConfigureAwait(false);

yield return 2;

}

Both MoveNextAsync() and DisposeAsync() are asynchronous methods. The await keyword should be used as demonstrated in the example.

Lazy Evaluation

As mentioned earlier, when a method uses the yield keyword, it generates an enumerable instance. The code within the method is executed only when the MoveNext() method of the enumerator is invoked, a concept known as “lazy evaluation.”

Understanding this behavior is crucial when dealing with parameter validation. Let’s consider the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

static IEnumerable<int> Range(int start, int count)

{

if (count < 0)

throw new ArgumentException("count must not be negative");

var end = start + count;

for (var value = start; value < end; value++)

yield return value;

}

This code requires the count parameter to be non-negative. However, there’s a potential issue with this when the validation occurs. If we execute the following code that calls the method with an invalid parameter and then use a foreach loop to iterate the enumerable:

1

2

3

4

5

Console.WriteLine("start");

var range = Range(0, -10);

Console.WriteLine("entering loop");

foreach(var item in range)

Console.WriteLine(item);

The output is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

start

entering loop

System.ArgumentException: count must not be negative

at Program.<<Main>$>g__Range|0_0(Int32 start, Int32 count)+MoveNext()

at Program.<Main>$(String[] args)

at System.RuntimeMethodHandle.InvokeMethod(Object target, Void** arguments, Signature sig, Boolean isConstructor)

at System.Reflection.MethodInvoker.Invoke(Object obj, IntPtr* args, BindingFlags invokeAttr)

Notice that, the exception is thrown only when the code enters the foreach loop. This happens because the validation is only performed when MoveNext() is called, which is called by the foreach. This behavior can be observed in SharpLab.

Parameter validation should occur when the method is called, not sometime later. To achieve this, the method should be split into two parts: one that does not use yield and another that does. This can be accomplished using a local function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

static IEnumerable<int> Range(int start, int count)

{

if (count < 0)

throw new ArgumentException("count must not be negative");

return GetEnumerable(start, count);

static IEnumerable<int> GetEnumerable(int start, int count)

{

var end = start + count;

for (var value = start; value < end; value++)

yield return value;

}

}

In this updated code, the portion of the method that is lazily evaluated has been moved into a GetEnumerable() local function. The Range() function first validates the parameter and then calls the local function.

The output for the previous test code is now:

1

2

3

4

5

6

start

System.ArgumentException: count must not be negative

at Program.<<Main>$>g__Range|0_0(Int32 start, Int32 count)+MoveNext()

at Program.<Main>$(String[] args)

at System.RuntimeMethodHandle.InvokeMethod(Object target, Void** arguments, Signature sig, Boolean isConstructor)

at System.Reflection.MethodInvoker.Invoke(Object obj, IntPtr* args, BindingFlags invokeAttr)

Importantly, it never reaches the enumerable instanciation. This behavior can also be observed in SharpLab.

Performance

If you’re concerned about performance considerations, it’s essential to be mindful of the following aspects:

Using yield generates an enumerable and its respective enumerator types. In most cases, enumerables are slower when compared to using the array indexer, spans, or types that implement IReadOnlyList<T> or IList<T>.

When employing yield, the method must return an interface. These represent reference types, and the performance may not be as optimal as with value type enumerators. Also, the enumerator is allocated on the heap.

Please refer to my other article titled “Performance of Value-Type vs. Reference-Type Enumerators in C#” for a detailed exploration of how enumerator types impact performance.

However, it’s worth noting that the lazy-evaluation nature of enumerables enables the generation of streams and their processing with minimal memory allocations, as demonstrated in the provided examples. yield remains a useful tool that can save substantial development and testing time. If you require enhanced performance for specific scenarios, consider exploring alternatives or implementing your custom enumerable solution.

For further insights into performance optimizations used by LINQ, I recommend checking out my article “LINQ Internals: Speed Optimizations”.

Coroutines

Coroutines are often described as functions with the capability to pause and later resume execution. In essence, they are methods that can be interrupted and continued, a behavior we’ve previously illustrated using enumerables and yield.

This concept finds extensive application in game development, particularly within the Unity framework. Game engines operate by executing code and then rendering frames, repeating these steps in a continuous loop. The rapid execution of this loop creates the illusion of movement, akin to a movie. Coroutines, in the context of Unity, are methods that enable the distribution of execution across multiple frames.

In Unity, a coroutine is essentially a method that returns IEnumerator. The Unity engine, in turn, invokes the corresponding MoveNext() method to resume execution just before each frame rendering. The utilization of yield simplifies code development and maintenance, eliminating the need to implement intricate state machines.

Here’s an example of a coroutine extracted from Unity’s documentation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

IEnumerator Fade()

{

var color = renderer.material.color;

for (var alpha = 1.0f; alpha >= 0.0f; alpha -= 0.1f)

{

color.a = alpha;

renderer.material.color = color;

yield return new WaitForSeconds(0.1f);

}

}

This coroutine smoothly decreases the alpha value of a material color by 0.1 every 0.1 seconds. It begins at 1.0 and ends at 0.0. Importantly, as this coroutine uses a timer, it’s unaffected by the framerate, ensuring consistent execution across various frames and rendering speeds.

Behavior Trees

Behavior trees find practical applications in game development and robotics, enabling the specification of agent or robot behavior in a modular and reusable manner. While initially designed for these domains, the concept can be extended to synchronously manage code execution in various computer science fields.

A behavior tree essentially comprises multiple nodes arranged in a tree structure. A node can exist in one of three states: Running, Succeded, or Failed. Consequently, a node is required to return an IEnumerable<BehaviorStatus>, with BehaviorStatus being a type that can represent these three states. A node must return either Succeded or Failed before its MoveNext() returns false.

A node with multiple children is known as a composite node, with one child is known as a decorator node, and a node with no children is known as a leaf node. Nodes with children are responsible for appropriately invoking the MoveNext() method of their children modules. In contrast, leaf modules perform specific, often application-customized, simple tasks. The hierarchical composition of multiple modules as a tree allows for the creation of complex tasks through their combination.

NOTE: Behavior trees cover a broad range of concepts. For further insights, you can refer to my other article titled “Behavior Tree Development in C# with

IEnumerable<T>andYield”.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the yield keyword in C# is a versatile tool offered by the compiler. While commonly used for creating collections and streams, its utility extends beyond that. It serves as a valuable resource for building easily maintainable state machines and offers a synchronous approach to managing code execution in various scenarios.