CPU branching and parallelization

Introduction

Performance depends not only on the logic of our own code but also, what the compiler does with it and how the CPU executes it.

Modern CPUs try to maximize its throughput by executing instructions simultaneously, while waiting for the result of logic tests. They try their best to guess the behavior of our code but, many times, the code has to be adjusted to maximize that potential. These optimizations are CPU dependent, and results may vary.

I want to acknowledge that this post is mostly based on knowledge shared by Bartosz Adamczewski.

Logical Branch Removal

“A branch is an instruction in a computer program that can cause a computer to begin executing a different instruction sequence and thus deviate from its default behavior of executing instructions in order.” — Wikipedia

Code execution on a CPU is not always linear. When it has to evaluate a condition to then decide what next instruction to execute, the CPU may try to guess the most probable branch to follow and execute ahead of time.

When the condition is finally evaluated, if it took the correct path, time was saved. Otherwise, it has to go back and take the correct branch, loosing valuable time. The more it predicts correctly, the better is the performance. Performance can be maximized when this decision making can be avoided.

For example, lets now implement an overload for Sum() that only sums the items to which the given predicate returns true:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public static int Sum(int[] source, Func<int, bool> predicate)

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in source)

{

if (predicate(item))

sum += item;

}

return sum;

}

In this case, the CPU will try to guess if it should add the value or not, but it has no knowledge of the data in source or the logical condition in predicate. This makes it almost impossible for the CPU to infer a heuristic.

One possible way of removing the logical condition is to convert the boolean to a number. It can be done very efficiently by using Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(). It converts, without copies or logic branches, the values false to 0 and true to 1.

NOTE: This assumes a

boolis internally represented as abyte. This may not be true for all implementations of .NET.

This number can now be multiplied by the item. This results in 0 being added to the sum when predicate is false; otherwise, the item is added.

Sum() can now look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public static int Sum(int[] source, Func<int, bool> predicate)

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in source)

{

var predicateValue = predicate(item);

sum += item * Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref predicateValue);

}

return sum;

}

NOTE: Not all logic branches were removed as foreach still generates an end condition which returns true for each item until it reaches the end. In this case, the CPU will be able to predict the branch most of the time. It should only fail at the end of the collection.

Let’s use BenchmarkDotNet to run the following benchmarks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using System;

using System.Runtime.CompilerServices;

public class BranchingBenchmarks

{

const int Seed = 0;

protected int[]? array;

[Params(20, 2_000)]

public int Count { get; set; }

[GlobalSetup]

public void GlobalSetup()

{

array = GC.AllocateUninitializedArray<int>(Count);

var random = new Random(Seed);

foreach (ref var item in array.AsSpan())

item = random.Next(Count);

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int If()

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in array!)

{

if (IsEven(item))

sum += item;

}

return sum;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Multiply()

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in array!)

{

var predicateValue = IsEven(item);

sum += item * Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref predicateValue);

}

return sum;

}

static bool IsEven(int item)

=> (item & 1) is 0;

}

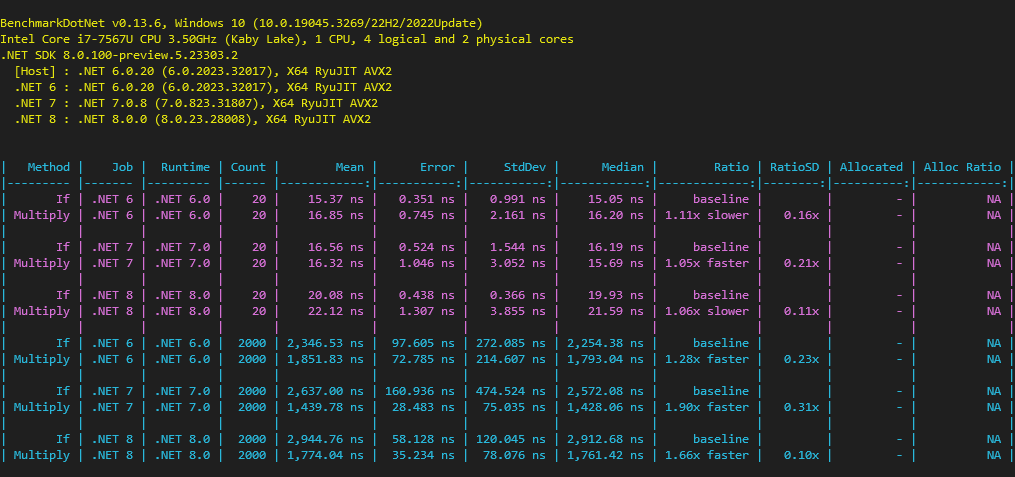

This benchmark tests the performance of each method using an array of random integers. It uses two lengths for the array: 20 and 2,000 items. Both methods sum only the values that are even.

NOTE: You can see in SharpLab that using

item % 2 is 0or(item & 1) is 0generates exactly the same assembly code on the latest .NET versions but not for the older versions. I’m using(item & 1) is 0to guarantee equality in the benchmarks.

NOTE: The results for this benchmark depend on how well the CPU can predict the branch to follow. This depends on the data used which, in this case, depends on the seed value.

For the given seed and given CPU, the Multiply() method is slightly slower for a short collection but 30% to 90% faster on a large collection. Please note that this means adding around 1 ns on a short collection but saving around 1,000 ns on a large collection.

You can find in this video other cases where you can apply this same logic:

Parallelization

I explain in my other article that CPUs can parallelize instruction execution by using SIMD, but it can also parallelize automatically in some other cases. These optimizations may not achieve the performance of SIMD but can be used when SIMD is not available or on the remaining items that don’t fill up a Vector<T>.

Let’s look into the simpler implementation of Sum():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public static int Sum(int[] source)

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in source)

sum += item;

return sum;

}

It adds all the items sequentially into a sum local variable. What if we use more than one local variable?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public static int Sum(int[] source)

{

var sum0 = 0;

var sum1 = 0;

for (var index = 0; index < source.Length - 1; index += 2)

{

sum0 += source[index];

sum1 += source[index + 1];

}

var isOddLength = (source.Length & 1) is not 0;

return sum0 + sum1 + (Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref isOddLength) * source[^1]);

}

This version iterates the array every two items, adding each item to two separate local variables. It then returns the addition of the two local variables and the last item if the length is an odd number.

NOTE: You can see in SharpLab that the JIT compiler is still smart enough to understand that bounds checking can be removed. I explain and benchmark this in my other article “Array iteration performance in C#”.

Let’s use BenchmarkDotNet again to run the following benchmarks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using System.Linq;

using System.Runtime.CompilerServices;

public class ParallelizationBenchmarks

{

protected int[]? array;

[Params(10, 1_000)]

public int Count { get; set; }

[GlobalSetup]

public void GlobalSetup()

{

array = Enumerable.Range(0, Count).ToArray();

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int ForEach()

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in array!)

sum += item;

return sum;

}

[Benchmark]

public int ForParallel()

{

var source = array!;

var sum0 = 0;

var sum1 = 0;

for (var index = 0; index < source.Length - 1; index += 2)

{

sum0 += source[index];

sum1 += source[index + 1];

}

var isOddLength = (source.Length & 1) is not 0;

return sum0 + sum1 + (Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref isOddLength) * source[^1]);

}

}

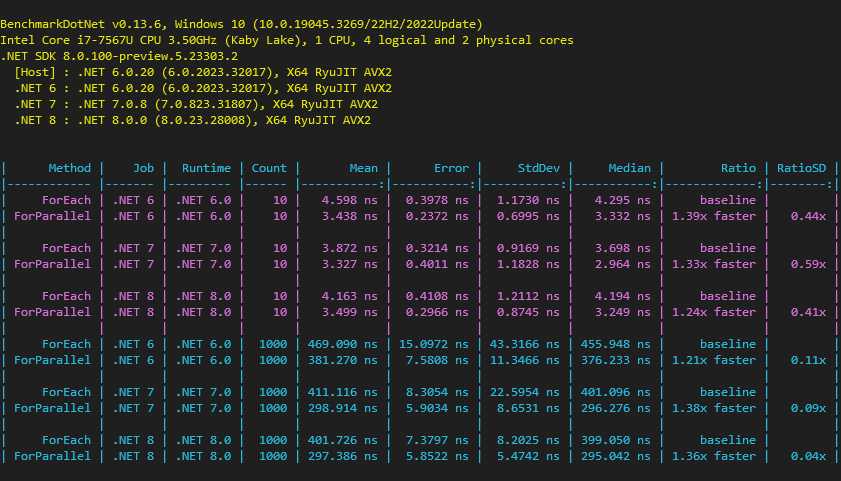

This benchmark tests the performance of each method using an array of integers. It uses two lengths for the array: 10 and 1,000 items.

The parallelized method is 20% to 40% faster for both short and large collections. Using this method, the CPU is able to automatically parallelize instruction flows.

All together now!

Let’s now implement Sum() with a predicate, using SIMD, logical branch reduction and parallelization:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

static int Sum2(int[] source, Func<int, bool> predicate, Func<Vector<int>, Vector<int>> predicate2)

{

var sum0 = 0;

var sum1 = 0;

var start = 0;

// check if hardware acceleration can be used

if (Vector.IsHardwareAccelerated && source.Length > Vector<int>.Count)

{

var sumVector = Vector<int>.Zero;

// cast the array of int to an array of Vector<int>

var vectors = MemoryMarshal.Cast<int, Vector<int>>(source);

// iterate on all vectors

foreach (ref readonly var vector in vectors)

{

// sum elements which the predicate value is -1

sumVector += Vector.BitwiseAnd(predicate2(vector), vector);

}

// sum all element of the vector

sum0 = Vector.Sum(sumVector);

// find what items were left unhandled

start = vectors.Length * Vector<int>.Count;

}

// sum all items not handled by hardware acceleration

for (var index = start; index < source.Length - 1; index += 2)

{

// use parallelization and logic branching removal to sum items

var predicateValue0 = predicate(source[index]);

sum0 += Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref predicateValue0) * source[index];

var predicateValue1 = predicate(source[index + 1]);

sum1 += Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref predicateValue1) * source[index + 1];

}

if ((source.Length & 1) is not 0) // source length is odd

{

// add the last item is predicate is true

var predicateValue = predicate(source[^1]);

sum0 += Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref predicateValue) * source[^1];

}

return sum0 + sum1;

}

This version requires one more predicate to be able take full advantage of SIMD. While the first one applies to a single item, the second one applies to a vector of items. Given a Vector<int>, it returns another Vector<int> with the values, 0 when the element is to be ignored, and -1 when the element is to be added.

Let’s use BenchmarkDotNet again to run the following benchmarks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using System;

using System.Numerics;

using System.Runtime.CompilerServices;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

public class HardwareBenchmarks

{

const int Seed = 0;

protected int[]? array;

[Params(10, 100, 1_000)]

public int Count { get; set; }

[GlobalSetup]

public void GlobalSetup()

{

array = GC.AllocateUninitializedArray<int>(Count);

var random = new Random(Seed);

foreach (ref var item in array.AsSpan())

item = random.Next(Count);

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int Baseline()

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in array!)

{

if (IsEven(item))

sum += item;

}

return sum;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Optimized()

{

var source = array!;

var sum0 = 0;

var sum1 = 0;

var start = 0;

if (Vector.IsHardwareAccelerated && source.Length > Vector<int>.Count)

{

var sumVector = Vector<int>.Zero;

var vectors = MemoryMarshal.Cast<int, Vector<int>>(source);

foreach (ref readonly var vector in vectors)

sumVector += Vector.BitwiseAnd(IsEven(vector), vector);

sum0 = Vector.Sum(sumVector);

start = vectors.Length * Vector<int>.Count;

}

for (var index = start; index < source.Length - 1; index += 2)

{

var predicateValue0 = IsEven(source[index]);

sum0 += Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref predicateValue0) * source[index];

var predicateValue1 = IsEven(source[index + 1]);

sum1 += Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref predicateValue1) * source[index + 1];

}

if ((source.Length & 1) is not 0)

{

var predicateValue = IsEven(source[^1]);

sum0 += Unsafe.As<bool, byte>(ref predicateValue) * source[^1];

}

return sum0 + sum1;

}

static bool IsEven(int item)

=> (item & 1) is 0;

static Vector<int> IsEven(Vector<int> items)

=> (items & Vector<int>.One) - Vector<int>.One;

}

It benchmarks both methods using an array of random integers. It uses three different lengths for the array: 10, 100 and 1,000 items. Both methods sum only the values that are even.

This time I used a configuration only for .NET 8 but with three variants:

- SIMD is not available (scalar),

- Vector128 is available,

- Vector256 is available.

The optimized version is significantly faster than the baseline version in all cases. It achieves more than a 7x gain for a 1,000 items array when Vector256 hardware is available.

Conclusions

Having a general knowledge of how a CPU works may allow major improvements in performance.