Performance of value-type vs. reference-type enumerators in C#

Introduction

The C# compiler generates different code for the foreach keyword, based on the collection type. When it uses the enumerator, it gets an enumerator instance by calling the GetEnumerator() method of the collection. The type returned by this method can be either a value type or a reference type. This can have major implications in the performance of the collection iteration.

NOTE: It uses the indexer in the case of arrays or spans. Check my other article “Array iteration performance in C#” to learn about those cases.

Reference-type enumerators

Classes and interfaces are reference types. If GetEnumerator() returns any of these then the enumerator is a reference type.

If the collection provided to foreach is of types IEnumerable or IEnumerable<T>, then the return type of GetEnumerator() is IEnumerator or IEnumerator<T> respectively. This means that the enumerator will be a reference type.

Enumerable.Range() is a method that returns IEnumerable<int>. Let’s use a foreach to iterate all the values of the collection:

1

2

3

var source = Enumerable.Range(0, 10);

foreach(var item in source)

Console.WriteLine(item);

You can see in SharpLab that the compiler converts this code to something equivalent to the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

IEnumerator<int> enumerator = Enumerable.Range(0, 10).GetEnumerator();

try

{

while (enumerator.MoveNext())

{

Console.WriteLine(enumerator.Current);

}

}

finally

{

enumerator?.Dispose();

}

It calls GetEnumerator() to get an instance of the enumerator. Notice that the enumerator is of type IEnumerator<int>, an interface.

It then uses a while loop with enumerator.MoveNext() as condition. Inside of the loop, it calls enumerator.Current to get the item.

NOTE: Because the

IEnumerable<T>derives fromIDisposable, it callsenumerator.Dispose()inside a finally to guarantee that it’s called even if an exception is thrown inside the loop.

You can also see in SharpLab the IL generated:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

IL_0000: ldc.i4.0

IL_0001: ldc.i4.s 10

IL_0003: call class [System.Runtime]System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerable`1<int32> [System.Linq]System.Linq.Enumerable::Range(int32, int32)

IL_0008: callvirt instance class [System.Runtime]System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerator`1<!0> class [System.Runtime]System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerable`1<int32>::GetEnumerator()

IL_000d: stloc.0

.try

{

// sequence point: hidden

IL_000e: br.s IL_001b

// loop start (head: IL_001b)

IL_0010: ldloc.0

IL_0011: callvirt instance !0 class [System.Runtime]System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerator`1<int32>::get_Current()

IL_0016: call void [System.Console]System.Console::WriteLine(int32)

IL_001b: ldloc.0

IL_001c: callvirt instance bool [System.Runtime]System.Collections.IEnumerator::MoveNext()

IL_0021: brtrue.s IL_0010

// end loop

IL_0023: leave.s IL_002f

} // end .try

finally

{

// sequence point: hidden

IL_0025: ldloc.0

IL_0026: brfalse.s IL_002e

IL_0028: ldloc.0

IL_0029: callvirt instance void [System.Runtime]System.IDisposable::Dispose()

// sequence point: hidden

IL_002e: endfinally

} // end handler

Notice that the instruction callvirt is used to call the MoveNext() and Current.

Value-type enumerators

Collections can implement a GetEnumerator() method that returns a value-type enumerator.

NOTE: Even if the collection implements

IEnumerable<T>, it’s possible to make it an explicit implementation, and add a public implementation that returns the value-type enumerator.

List<T> is one example of these enumerables. Let’s use a foreach loop to iterate all the values of the collection:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

List<int>.Enumerator enumerator = new List<int>().GetEnumerator();

try

{

while (enumerator.MoveNext())

{

Console.WriteLine(enumerator.Current);

}

}

finally

{

((IDisposable)enumerator).Dispose();

}

The code is very similar to the case of reference-type enumerator but notice that now the enumerator type is of type List<int>.Enumerator. You can see in GitHub that this is a value-type.

You can also see in SharpLab the IL generated:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

IL_0000: newobj instance void class [System.Collections]System.Collections.Generic.List`1<int32>::.ctor()

IL_0005: callvirt instance valuetype [System.Collections]System.Collections.Generic.List`1/Enumerator<!0> class [System.Collections]System.Collections.Generic.List`1<int32>::GetEnumerator()

IL_000a: stloc.0

.try

{

// sequence point: hidden

IL_000b: br.s IL_0019

// loop start (head: IL_0019)

IL_000d: ldloca.s 0

IL_000f: call instance !0 valuetype [System.Collections]System.Collections.Generic.List`1/Enumerator<int32>::get_Current()

IL_0014: call void [System.Console]System.Console::WriteLine(int32)

IL_0019: ldloca.s 0

IL_001b: call instance bool valuetype [System.Collections]System.Collections.Generic.List`1/Enumerator<int32>::MoveNext()

IL_0020: brtrue.s IL_000d

// end loop

IL_0022: leave.s IL_0032

} // end .try

finally

{

// sequence point: hidden

IL_0024: ldloca.s 0

IL_0026: constrained. valuetype [System.Collections]System.Collections.Generic.List`1/Enumerator<int32>

IL_002c: callvirt instance void [System.Runtime]System.IDisposable::Dispose()

IL_0031: endfinally

} // end handler

Notice that the instruction call is used to call the enumerator methods.

NOTE: The instruction

callvirtis used to callDispose()but, because of thecontrained.instruction in the line before, the assembly generated will be similar to thecallinstruction.

Benchmarking

Let’s use BenchmarkDotNet to run the following benchmarks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

public class ValueTypeEnumerator

{

List<int>? list;

IEnumerable<int>? enumerable;

[Params(100, 10_000)]

public int Count { get; set; }

[GlobalSetup]

public void GlobalSetup()

{

list = System.Linq.Enumerable.Range(0, Count).ToList();

enumerable = list;

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int Enumerable()

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in enumerable!)

sum += item;

return sum;

}

[Benchmark]

public int List()

{

var sum = 0;

foreach (var item in list!)

sum += item;

return sum;

}

}

It compares the performance of iterating a List<int> with 100 and 10.000 items when cast to IEnumerable<int> (reference-type enumerator) and when directly using List<int> (value-type enumerator).

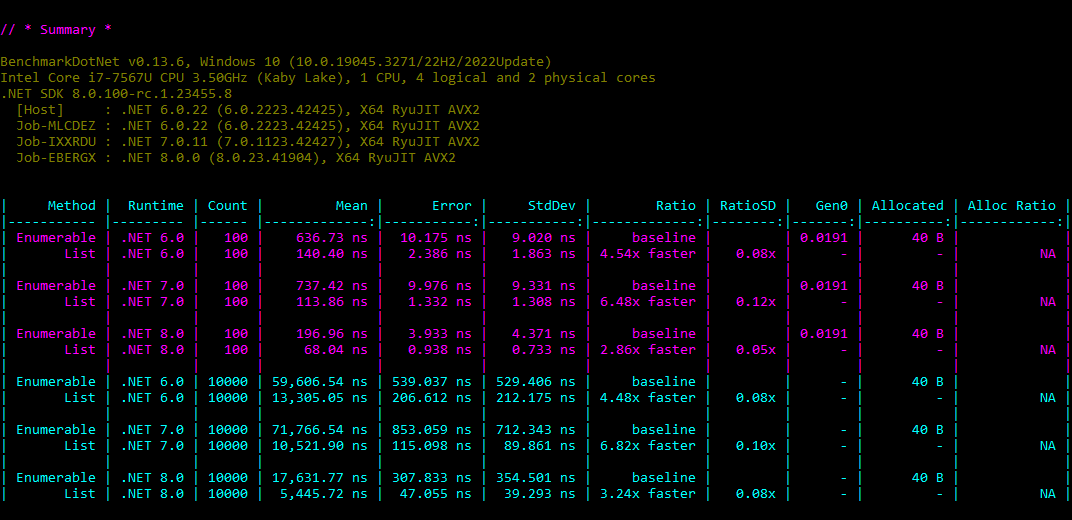

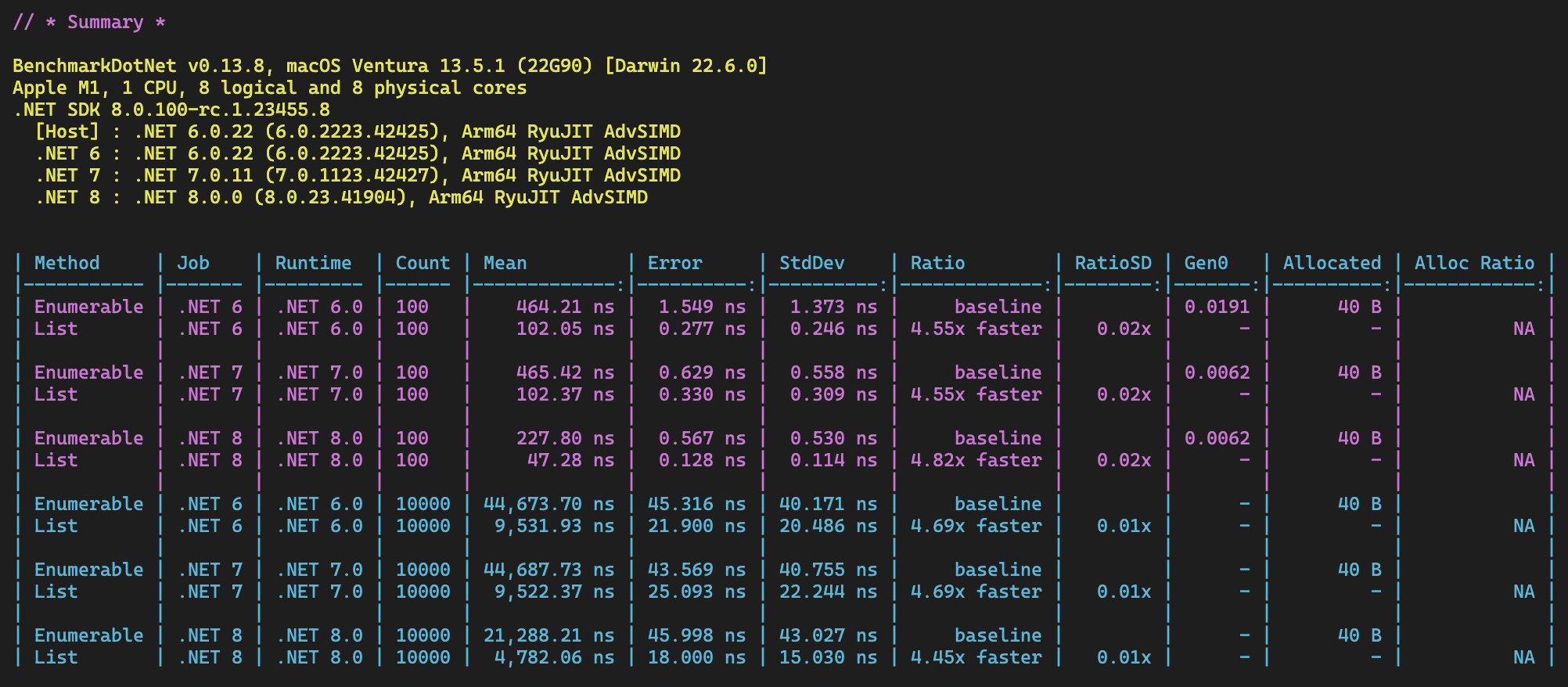

I used a configuration to test on .NET 6, .NET 7, and .NET 8 RC1 (all “modern” NET versions).

Notice that the difference ranges from 300% and 700% on x64 and a steady 450% on Arm64. Value-type enumerators always performing better than reference-type enumerators.

Also notice that value-type enumerators do not allocate on the heap, not adding pressure to the garbage collector. One other thing to note is that the performance improves significantly between .NET 7 and .NET 8. That’s one good reason to upgrade to .NET 8 as soon as possible.

Conclusions

Virtual calls are required in types that support inheritance. Value types in .NET do not support inheritance so all methods are called directly. When a value-type is cast to an interface, it’s copied into the heap and converted to a reference type (boxing).

Iterating a collection means calling MoveNext() and Current for each item. Using a value-type enumerator may make a huge difference in performance for large collections.

When using a collection avoid casting it to an interface. On public APIs, consider using immutable collections. All collections provided by the .NET framework make use of value type enumerators. If you implement a new collection type, don’t forget to do it also.